The paper in npj Digital Medicine is here: go.nature.com/2Augklz

As a clinician, I am rarely the sole provider of my patients’ care. The clinical decisions I make exist as part of a patient’s healthcare journey, of which I am one of an ensemble cast of physicians, surgeons, family doctors and allied health professionals.

I can’t command expertise across the breadth of human disease, and nor can any of my colleagues. We partition medical knowledge into our own siloes of specialisation. To give my patients the best possible care, I must be aware of the actions, thoughts and intentions of my clinical colleagues.

The National Health Service in England, despite being publicly funded through a single, government payer, is formed of a patchwork of electronic health record vendors, with many centres still relying on paper. Previous efforts to achieve a national data sharing framework in 2013 were abandoned amidst concerns around its cost, privacy and security. Attempting such a nationally comprehensive, interoperable clinical information system in the near future seems politically unpalatable and financially prohibitive.

Instead, clinic visits in England today are punctuated by apologies from doctors that their patient’s test results are unavailable, while patients regret not bringing the ‘right piece of paper’ given to them by another hospital. Care is delayed, investigations are duplicated and errors occur.

In our paper, we explore the notion that hospital care, despite being part of a national organisation, is fundamentally a local phenomenon. If patients receive care at multiple hospitals, most of those hospitals will be near to one another. We used hospital administrative data for England in 2013-15 to examine how frequently pairs of hospitals provided care to the same patients.

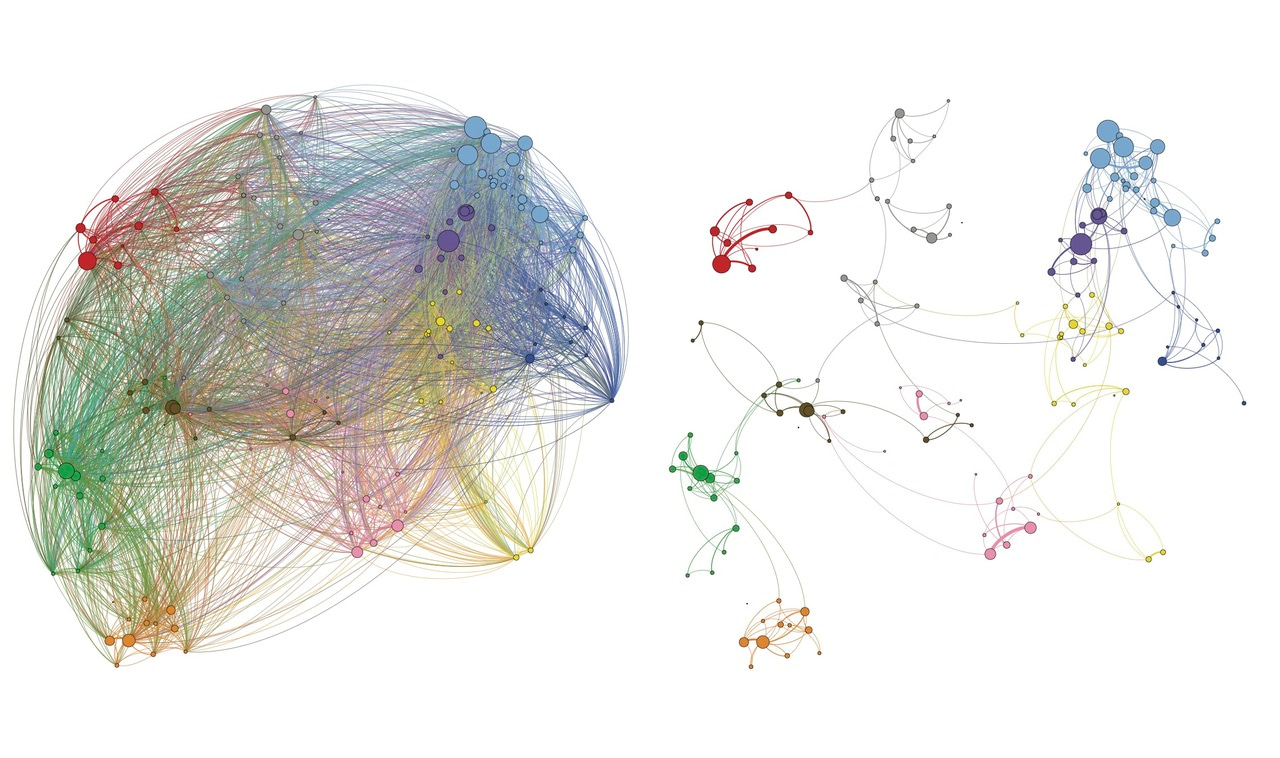

We found that patient-sharing is common. On 15 million occasions patients attended one hospital having attended a different hospital on their last visit. In some parts of England, as many as 30% of clinical presentations are shared in this way. Where care is shared between hospitals, those hospitals are usually close neighbours. This insight enabled us to use Markov Multiscale Community Detection, a network analysis technique, to partition our patient-sharing network into ten discrete communities of hospitals that were most likely to share patients amongst each other.

If clinical data were shared between hospitals within each of these regional communities, when patients present to different hospitals, the relevant clinical data would be available to clinicians on between 65% and 95% of occasions. At most, only 24 hospitals would be required to share data with one another, instead of the 155 hospitals in a nationally interoperable system.

Regional data-sharing strategies, like the ones we propose, make a great deal of sense to patients, clinicians and politicians alike. Data should not be shared between hospitals that don’t share patients. Doing so risks a security breach, without any foreseeable benefit to patients.

Aiming for a costly, far-off nationally interoperable health data system goes against the findings of our paper, that healthcare is a local, spatially clustered phenomenon. It is time to develop regional data-sharing strategies that reflect how our health system really works, rather than the grand ambitions of policymakers.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in